Value investing was built on discipline: buy cheap, insist on a margin of safety, and sell when the market gets carried away. For multiple generations of value investors, that mindset worked beautifully. It kept emotions in check, avoided overpaying, and turned constant volatility into plentiful opportunity.

But in the 21st century the most disciplined value investors, the ones who pride themselves on prudence, have been struggling to find the same types of bargains as they had in the 20th century. The strategy is to buy ‘ok’ businesses when they get undervalued, then sell them when the valuations look a bit rich. On paper, it feels like they’re doing the right thing, and any back-testing that includes the times of Benjamin Graham displays outperformance. But this approach often misses the vast wealth creation that happens at the best companies over the long term.

From Graham’s Cigar Butts to Buffett’s Wonderful Companies

Benjamin Graham’s philosophy was to buy $1 for 50 cents. But his most prodigious student – Warren Buffett, influenced by Charlie Munger, took it further. He realized that it’s often better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.

The reason is simple: great businesses compound internally. They don’t need you to time the market or guess when to sell. They take retained earnings and reinvest them at high returns, quietly building intrinsic value year after year. Companies like Coca-Cola, American Express, Visa, Costco, and other durable franchises have rewarded shareholders, for the most part, not because they could be acquired cheaply, but because their underlying economics were so powerful that time itself became the ally.

If you had simply bought and held these businesses, most of the work would have been done by the business, not by you picking the best buy and sell moment.

The Value Investor’s Round Trip

Here’s where many traditional value investors run into trouble. They buy when something looks cheap, and when it gets expensive by their standards, they sell. That sounds logical. But it usually leads to what you might call a “round trip.”

- They sell and pay transaction costs

- Then pay taxes on their gains

- And now need to find another great idea, which is rarely another “under-valued American Express”. Meanwhile, the company they sold keeps compounding earnings and intrinsic value.

They save themselves from a temporary 20 percent drop when a stock cools off, but they miss out on the next ten years of compounding.

This is what Peter Lynch has called “cutting the flowers and watering the weeds”.

Compounding Happens Inside the Great Business

A superior business keeps redeploying capital into projects and opportunities that earn high returns. The investor’s job is to identify those rare businesses and then let them do their thing.

Overvaluation comes and goes. Buffett has held onto companies like Coca-Cola through long stretches where the multiple looked high because he trusted the business to keep growing its value per share. The market’s moods shift from overvalued to way overvalued and back again, but over the long run, the returns tend to follow the company’s compounding power, not the short-term valuation swings.

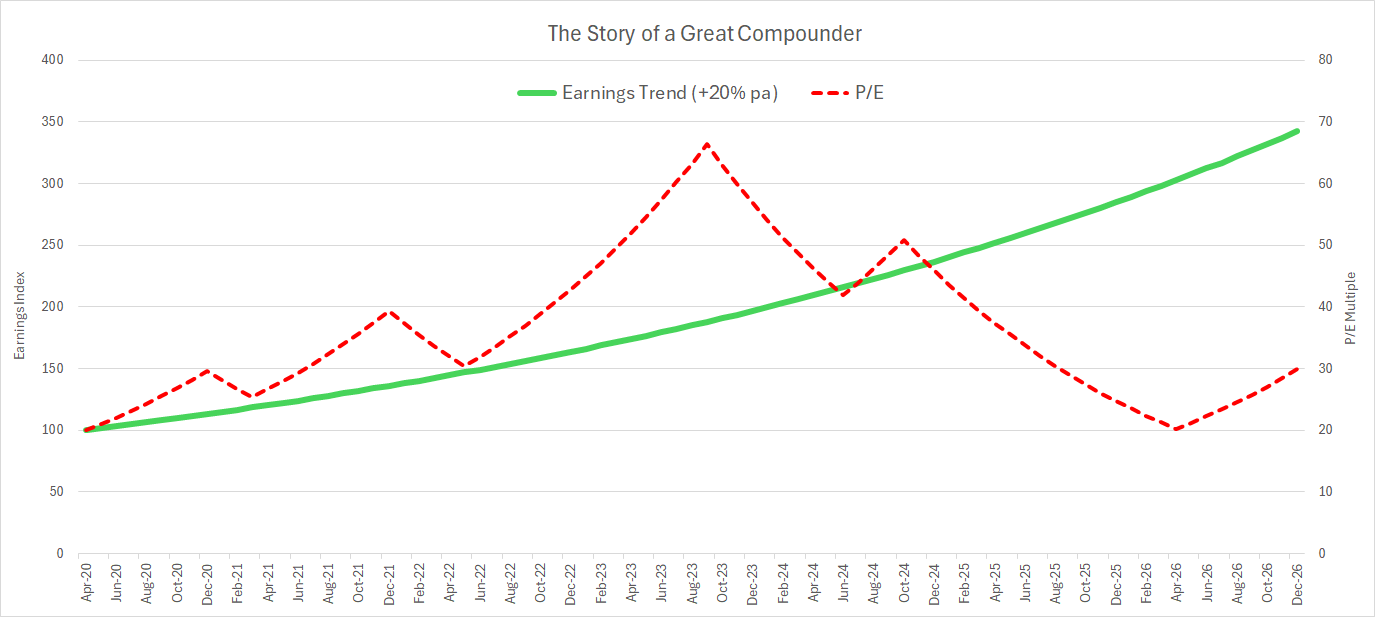

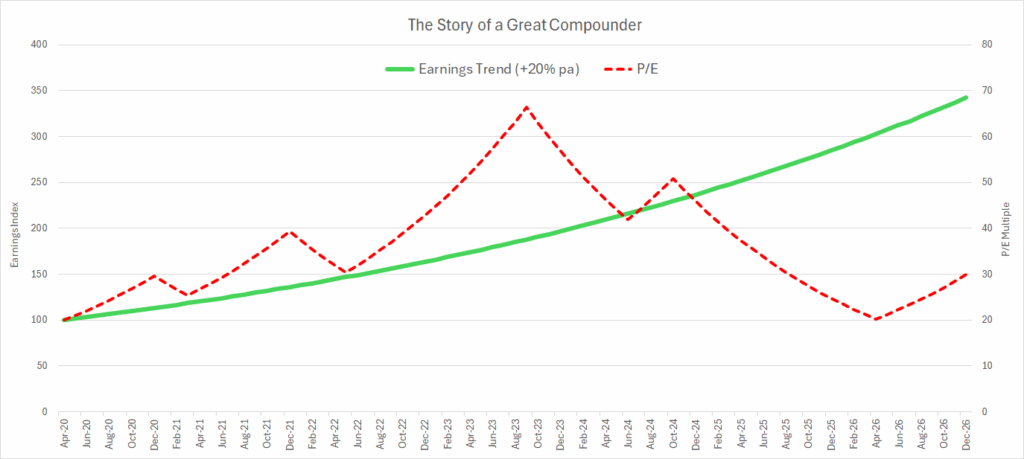

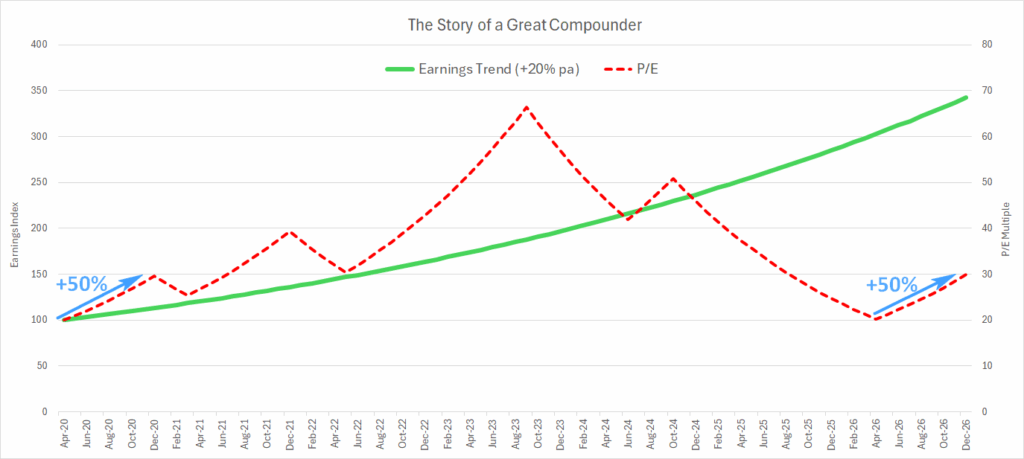

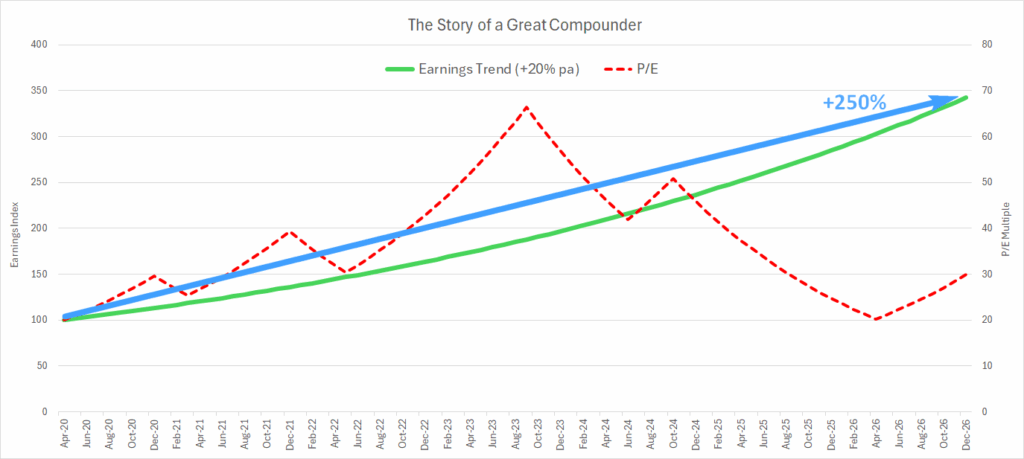

Let’s imagine an example of these Great Compounders going through the typical earnings and P/E growth story:

The Cost of Being Out

It’s easy to calculate the cost of holding a mediocre business too long. What’s harder is measuring the cost of not holding an exceptional one. Selling a world-class compounder can be one of the most expensive mistakes an investor makes.

Think of people who sold Apple in 2013 because it looked “fully valued” or those who trimmed Costco in 2018 when it was trading at a premium multiple. They might have looked smart in the short run, but they gave up years of double-digit growth, rising shareholder yield, and consistent value creation. Add in the capital gains taxes, and the new stock they bought had to outperform by a wide margin just to break even with what they gave up.

The typical value buyer of American Express, Coca-Cola, or more recently Apple or Google, might summon the courage to start a position when the Great Compounder’s P/E multiple dips down to 20 and then gleefully ‘take profit’ when the P/E jumps up to 30. If they’re lucky they might get blessed with a couple of these opportunities on our example of a Great Compounder and come out with a total gain of some +80% post costs and taxes.

The Discipline of ‘Watching Paint Dry’

One of the hardest lessons for a value investor is that sometimes the most disciplined move is to do nothing. Once you own a business with durable advantages, good reinvestment opportunities, and honest, capable management, your best play might simply be to hold on and let compounding work.

Patience isn’t laziness. It’s conviction. It’s foresight. It’s the quiet confidence to let time do what skill and (hyper)activity can’t always improve.

In our example that would let the investor bag a +250% return on the company’s fundamentals, and as the entry price was great – an even higher total return.

I Agree – This is Hard

Modern value investing doesn’t mean abandoning valuation discipline. It means expanding what we mean by value. Value can come from cheapness, but it can also come from quality, staying power, and the ability to reinvest for decades. The fair price of a wonderful business often turns out to be a much better bargain than the rock-bottom price of an average one.

The real art is in finding that balance: knowing when to buy with a margin of safety, and knowing when not to interrupt a compounding machine that’s working beautifully.

This is, indeed, hard.

It might not be in your ‘circle of competence’.

But don’t dismiss this approach out-of-hand just because “Benjamin Graham says – ‘Buy Net-Nets’”.

In the end, even Graham turned to and succeeded in buying ‘Wonderful Business at a Fair Price’:

“What happened is that low-hanging fruit eventually went away as the aftermath of The Great Depression got away. And then Graham actually made more than half of all the money he made in his life out of one stock, and that stock was GEICO, which was a great business.”

Charlie Munger, Daily Journal Shareholders Meeting 2023